Steps

Structured decision making (SDM) is a organized approach for helping people work together to make informed and transparent choices in complex decision situations. Rooted in the decision sciences, it is a learning-focused process based on seven core steps:

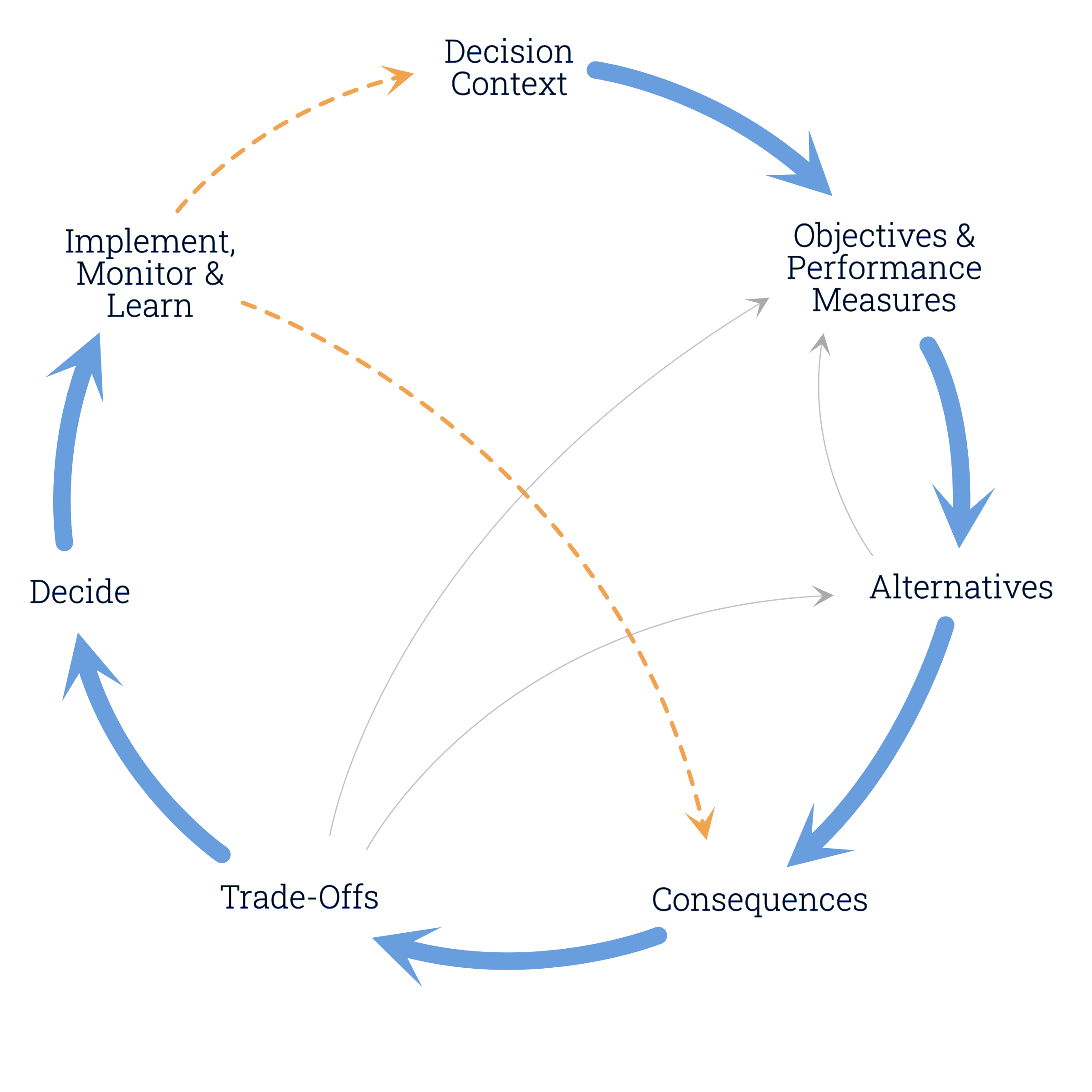

A good decision process is iterative (grey arrows) – learning at later steps often causes refinement to earlier work, and on complex decisions participants may work through several rounds of evaluation. When SDM is used to make recurring decisions over time (orange arrows), it’s sometimes called adaptive management.

What exactly is done at each step, to what level of rigour and complexity, will depend on the nature of the decision, the stakes and the resources and timeline available. In some cases, the appropriate analysis may involve complex modeling that has been the subject of years of fieldwork; in others, it will involve structured elicitations of expert judgment conducted over several days. In still others, a careful structuring of objectives and alternatives may be all that is needed to clarify thinking around a particular decision and a qualitative analysis will suffice. A key point is that structured methods don’t have to be time consuming; even very basic structuring tools and methods can help to clarify thinking, minimize errors and biases, and ensure that the technical and values basis for difficult decisions is transparent and defensible.

Step 1

Decision Context

Practice Notes & Tools

The first step in SDM is to clarify the decision context. What is the underlying problem or opportunity? What is the decision to be made and who will make it? What is the scope or limitations of the process and the decision (i.e., what’s in and what’s out of scope?) What are the real constraints for the process (timelines, budget, legal issues)? What kind of technical analysis is going to be needed? Who needs to be involved in developing solutions, and how will they work together?

This step has three main tasks: framing the decision, sketching the decision, and designing the decision process. Often overlooked, this step is both harder than it looks, and critical to good decision making.

There are usually several different ways the decision could be framed. The challenge is making sure it’s framed in a way that addresses the underlying problems, recognizes institutional complexities, and challenges assumptions while accepting hard constraints. A common error is framing a decision problem too narrowly, which limits the ability to solve the problem creatively. Another challenge in many organizations or governments, or in a multiparty context, is that everyone comes to the table with different assumptions about the decision frame.

Decision sketching (sometimes called or rapid prototyping) involves running through the SDM steps at a scoping level. It helps clarify the focus and frame of the decision, and confirm that everyone involved has a common understanding. Sketching provides important insights into what information is going to be required, who is going to be affected and therefore needs to be engaged, and who the ultimate decision maker(s) will be and what their needs are. While most resource management decisions are multi-objective decisions and will benefit from working through all the steps of SDM, they may vary significantly in the amount of attention needed at each step. The sketch will reveal for example, if the decision is going to need a focus on uncertainty and predictive ability, or tools for developing complex alternatives, or analytical methods for dealing with multiple interconnected decisions, all of which suggest different kinds of analytical and facilitative capacity needs than problems where the central challenges are related to conflicts about value-based trade-offs.

Following a decision sketch, a process design, along with a detailed work plan and budget can be developed to guide the necessary analytical and engagement work. These can be captured in a decision charter.

Step 2

Objectives & Performance Measures

Practice Notes & Tools

At the core of an SDM process is a set of well-defined objectives and measures that clarify “what matters” – the things that people care about and could be affected by the decision.

Objectives for decision making are different from other kinds of objectives. They are simple statements of the values or concerns that are at stake in the decision. Measures (also called attributes, performance measures or evaluation criteria) are the specific metrics that will be used to estimate/model and report the consequences or performance of the alternatives on the objectives.

It takes some effort to develop a good set of objectives and select appropriate measures. A key task is separating means and ends. Not unlike separating interests from positions, this is a critical task that ensures that the decision is structured in a way that is consistent with the principles of decision science, and more importantly, that will lead to useful insights and productive, value-focused deliberations for stakeholders and decision makers.

Together, objectives and measures drive the search for creative alternatives and become the framework for comparing alternatives. They help a group to prioritize and streamline information needs, as data gathering, modeling and expert processes are focused on producing decision-relevant information. They become the focus of value-based deliberations about key trade-offs and uncertainties. Taking time to get them right is a critical step worth investing in.

Step 3

Alternatives

Practice Notes & Tools

Alternatives are the various actions or interventions that are under consideration. In some contexts, alternatives are easy to identify (e.g., alternative habitats to restore, alternative community projects to fund, etc.) and the work is in evaluating them. In many environmental management contexts however, the alternatives are complex sets of actions that need to be thoughtfully developed (e.g., alternative ways of managing a park, sharing water, or sequencing development). Often, it’s useful to combine groups of actions into discrete strategies for comparison.

The work typically involves iteratively developing alternatives (step 3), estimating their consequences (step 4), evaluating trade-offs (step 5) and then, based on what is learned, returning to develop more refined or hybrid alternatives that offer a better balance across the objectives. Decision support tools (e.g., color-coded consequence tables, pair-wise comparisons, dominance and sensitivity assessments, etc.) can be used (see steps 4 and 5). Poor performers are eliminated from further consideration, and desirable elements from different alternatives may be combined to create new ones.

Often there are several rounds of identifying and evaluating alternatives as more is learned (through modeling and other methods of consequence assessment) about how well different combinations of actions work. It’s usually important to have one or more reference cases, which may include for example, a business-as-usual case (projecting a continuation of current practices), BAU under various future climate scenarios, current conditions, and/or historical condition. An emphasis on reporting the consequences of alternatives relative to these reference cases provides important context for evaluating the significance of trade-offs.

Creating and evaluating a range of well-defined, internally coherent alternatives is central to good decision making. In public planning processes, having stakeholders participate in the process of alternatives creation is important both for ensuring that a wide range of possible solutions to the problem are heard and explored, and for ensuring participant buy-in of the process. In complex decisions, however, alternatives may require considerable effort to develop and describe properly. Useful tools for co-creating alternatives include value focused thinking, conceptual models of cause and effect, strategy tables and portfolio builders.

A good range of alternatives will reflect substantially different approaches to a problem based on both different technical or policy approaches, and different priorities across objectives. In many environmental management contexts, it may be important to search for alternatives that are robust to key uncertainties or that are likely to reduce them over time.

Step 4

Consequences

Practice Notes & Tools

This step involves using the best available evidence and critical thinking to describe the predicted consequences of the alternatives.

For some objectives, characterizing consequences may involve using complex hydrological, ecological, or socio-economic modeling; for others, it may involve eliciting expert judgment to estimate consequence values, assign relative scores or provide narrative descriptions. Depending on the context, experts may come from diverse domains and systems of knowledge, including Indigenous and local knowledge, as well as science, economics or engineering. Sometimes we use a relatively simple approach to characterizing consequences in a first pass, and refine the details as needed later in the process.

Conceptual models (e.g., influence diagrams, impact pathway diagrams, etc.) are figures that illustrate cause and effect pathways and competing hypotheses that link the things managers can do (alternatives) to the things we care about (objectives). They are useful for building a shared understanding of how causes and effects link up, and promote effective conversations among people with different mental models or different levels and kinds of expertise.

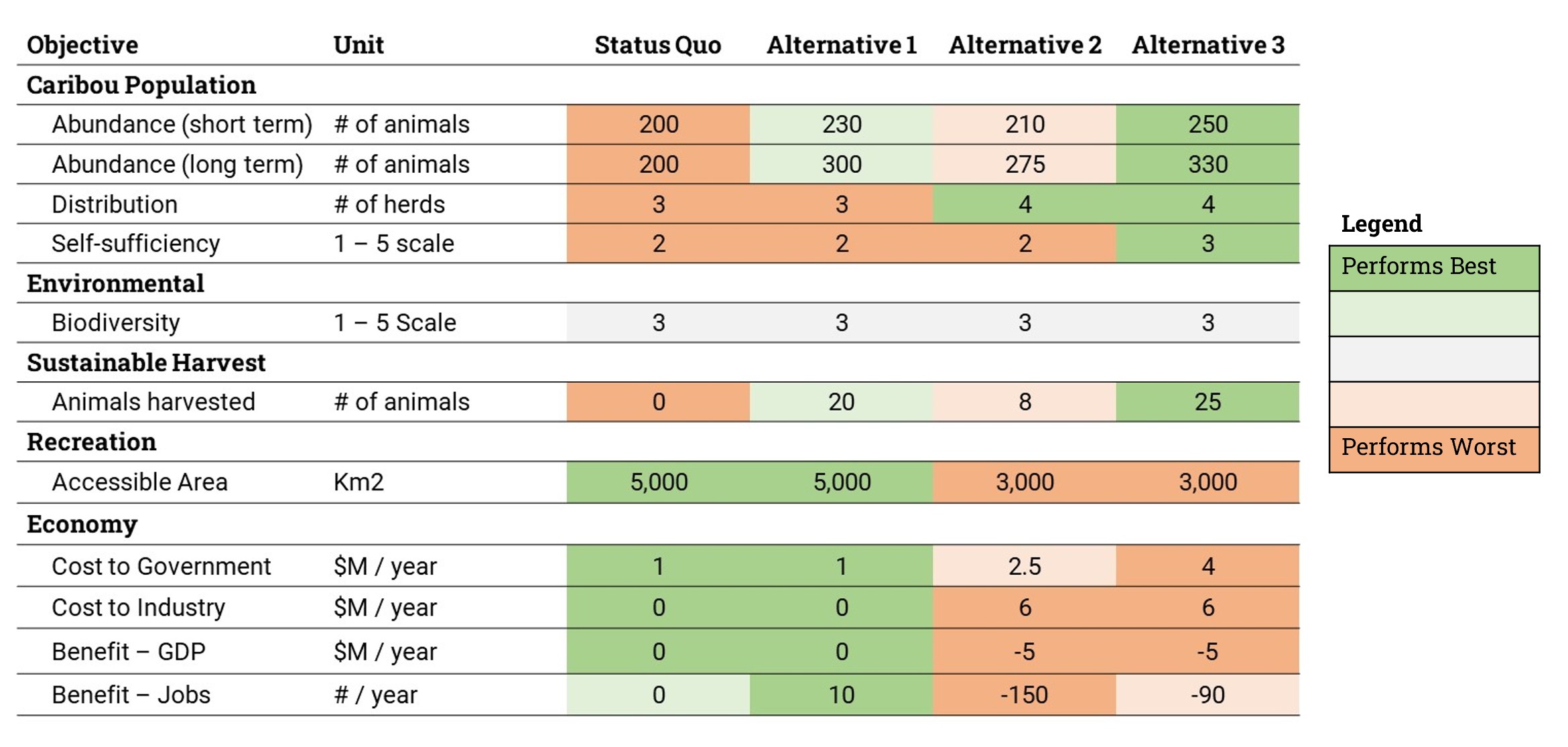

Results are typically presented in a consequence table, which summarizes the expected performance of each alternative with respect to each decision objective, as reported by the performance measures. The table creates a shared understanding of how different alternatives affect different objectives, and it exposes key trade-offs across the objectives. If there are uncertainties that affect the selection of a preferred alternative, these should be reflected in the consequence table so that decision makers can make choices that reflect their risk tolerance or risk attitudes. The process of populating a consequence table involves important shared learning about what is known and not known about potential outcomes. It highlights and focuses decision makers on key value-based trade-offs.

One of the important functions of consequence table is that it separates technical judgments (the estimates of consequences in the table), which should be made by people with specialized knowledge, and value judgments (opinions about the selection of a preferred alternative), which should be made by stakeholders and decision makers, and do not require specialized knowledge. This helps to democratize decision making by ensuring that anyone affected by the decision, regardless of their level of technical expertise, can participate in deliberations and make informed value judgments based on the best available knowledge.

A colour-coded consequence table can be helpful in highlighting differences across the alternatives. Here, dark green cells indicate the best performance for an objective, while dark orange cells indicate the worst performance.

Step 5

Trade-Offs

Practice Notes & Tools

At this stage, the goal is to find the alternative that offers the best balance across the objectives, in consideration of the diverse values and perspectives of the affected parties. This step involves thinking and talking about difficult value-based trade-offs, clarifying preferences and the reasons for those preferences, and seeking a solution that can be broadly supported.

When we use the term ”trade-offs”, we simply mean the situation where there is at least one pro and at least one con between at least two alternatives. Before we can say that one is “better” than the other we have to make a judgment call based on our values. In a supermarket, if one apple is fresh and costs $1, but another is less fresh and costs $0.50, and all else is equal, which is best? The answer is, it depends – on how important the difference in freshness and $0.50 are to whoever you’re asking. Reasonable people may disagree on which apple is best given this trade-off: there’s no correct answer.

Essentially, SDM focuses people on key trade-offs across alternatives in an effort to find an alternative that everyone can support. The emphasis on trade-offs may feel unusual, but it really is at the heart of good decision making. If a group is serious about trying to find a mutually acceptable outcome, a focus on trade-offs helps to:

- Identify alternatives that are simply not efficient (that is, they are sub-optimal in that they can be improved in one or more respects without causing a decline in others)

- Provide insight on new or hybrid alternatives

- Learn the limits of the irreducible trade-offs that exist between alternatives (where there’s no way to improve the performance of X performance measure without also reducing the performance of Y or Z)

- Prepare the basis for difficult and meaningful conversations about finding the alternative with the “best” balance of performance given the constraints of the decision context.

A good deliberative trade-off process emphasizes respectful reason-giving, reflection and learning. Structuring tools and professional facilitation can help to expose errors of logic and reasoning, promote co-learning, build a broader appreciation of the perspectives of others, and improve the consistency and transparency of choices.

So how do we do it? A first step in evaluating trade-offs is to try to simplify the consequence table by checking for insensitivity and dominance. That is, by hiding performance measures that don’t vary across the whole range of alternatives, and removing any alternatives that are fully out-performed by another.

Next, it can be helpful to walk participants through a series of paired comparisons. This is a deliberative approach in which attention is drawn to the trade-offs (the pros and cons) between any two of the alternatives, and the conversation is focused on clarifying preferences – can we agree that one alternative is “better” than another? Sometimes this process leads directly to the identification of a preferred alternative. In other cases, new alternatives are suggested through discussion which may result in another round of evaluation.

If the decision is particularly complex or there are challenges in reaching a broadly supported decision, a variety of methods from the decision sciences are available to support deliberations. For example, it may be useful to use formal preference assessment methods for explicitly weighting the measures and deriving scores and ranks for the alternatives. In groups who share similar values, it might be possible to agree on a set of weights for the measures, and use calculated performance scores to quantitatively rank the alternatives. In many groups however, people will have such diverse values that agreeing on or averaging weights is neither possible nor useful. In this case, some practitioners use preference assessment methods not as a way to calculate the best alternative, but rather as a way to support and inform the deliberative process. For example, the results can help to identify and challenge hidden biases, to clarify sources of agreement and disagreement (do participants disagree about facts or values, for example), and to focus and structure dialogue in ways that support collaborative, interest-based decision making.

Sometimes this deliberative exploration of trade-offs leads seamlessly to a preferred alternative. Other times, it leads to the development of new and better alternatives, and another round of evaluation occurs.

Step 6

Decide

Practice Notes & Tools

Once participants in the SDM process have explored a reasonable range of alternatives and deliberated about key trade-offs and uncertainties, they should have the information they need to make an informed choice [1]. At this point, they are asked to confirm their degree of support for the short-listed alternatives. Relatively simple but explicit support polling minimizes the possibility for later misunderstandings about who is agreeing to what and why, and provides important information to decision makers. It can be helpful in establishing if there is a consensus, and if not, whether something could or should be done about that.

What happens next, including the role and importance of consensus, varies depending on the decision context. Many SDM processes are advisory in nature. Accordingly, they seek but do not require consensus. In these cases, decision makers are briefed on the process, they deliberate about the irreducible trade-offs and uncertainties, and make final decisions.

Some SDM processes occur in a shared decision making context. That is, the people at the SDM table have the authority and the responsibility to make a final decision together. In these cases, the role of consensus is obviously critical – without it, there is no decision. In this case, the iterative process of identifying alternatives, deliberating about trade-offs, improving and re-evaluating alternatives, continues until a solution is found that all parties can agree to. In the absence of a mutually acceptable solution, the parties may have formal procedures for dispute resolution that can be invoked. Alternatively, the parties may agree to park the decision. If the decision is parked, the reasons for the failure to agree should be carefully documented. This may enable the parties to efficiently revisit the decision some time in the future.

Regardless of who makes the decision or how, the structure and clarity of an SDM process provide a basis for transparently documenting the decision process and communicating the reasons, including the difficult value trade-offs that were made by decision makers. This includes documenting all of the alternatives that were considered along the way, and the reasons why they were rejected or modified. This goes a long way to support transparency and accountability in public decision making.

[1] Earlier versions of the SDM cycle did not include a step for Deciding. Rather the act of deciding was embedded in the task of Evaluating Trade-offs. However, practitioners increasingly distinguish between evaluating trade-offs and formally deciding. Some frameworks combine Deciding with Implementing. Others, as reflected here on SDM.org, view Implementation as tightly linked with Monitoring and Learning, and combine these three in the final step.

Step 7

Implement, Monitor & Learn

Practice Notes & Tools

Effective implementation involves many sector-specific technical, logistical, communication and engagement considerations that are beyond the scope of SDM as a field of practice. That said, implementing in a way that promotes learning is central to improving decisions over time, and thus monitoring and learning, and revisiting decisions based on what is learned, are core parts of SDM practice.

Monitoring the outcome of implementing a decision at some level is almost always valuable. There are various purposes for monitoring, but most of them relate to learning from the experience or establishing better information to inform future decisions. Key reasons for conducting monitoring are:

- Confirming that decisions are implemented in accordance with commitments made during an SDM process

- Assessing the current state of the system to determine which action to take (e.g., if different actions are taken in dry years vs. wet years)

- Evaluating the effectiveness of management actions

- Comparing outcomes to predictions (made in Step 4) to learn about the system and inform future decisions

Monitoring can also provide data that helps test hypotheses or reduce uncertainties identified in the decision process. Where uncertainty about outcomes affects the selection of a preferred action, a commitment to structured learning over time and a pledge to formally review the decision when new information is available can be the keys to reaching agreement on a way forward. An initial SDM process can thus transition to a formal adaptive management process. Linking monitoring programs to the objectives and performance measures used to evaluate management alternatives will help to ensure relevance to future decisions. In the diagram above, the orange arrow linking this step to Consequences represents this iterative aspect of adaptive management.

Many SDM processes also result in recommendations for new governance for oversight of monitoring programs and include triggers for review and mechanisms for amendments. The second orange arrow in the diagram above (back to Step 1) reflects those situations when monitoring or other triggers reveal a need to revisit the decision context itself.

A commitment to learning is one of the things that sets SDM apart as a framework for planning and decision making. It occurs not just at Step 7, but throughout the process. Participants need to be prepared to listen and learn about others’ values, to explore competing hypotheses about cause-effect relationships, and to build a common understanding of what constitutes the best available information for assessing consequences. This forms the basis for working collaboratively on solutions. In this final step, the focus is on the learning that is needed to improve future decision making. The challenge is to implement the decision in a way that reduces uncertainty, improves the quality of information for future decisions, and provides opportunities to revise and adapt based on what is learned.

How does SDM support better decisions?

SDM doesn’t make hard choices easy. It does make them more explicit, informed, transparent and efficient. It does this by: